The sound of the church-going-bell, summoning the faithful to Mass, had not been heard reverberating among the hills and valleys…..

So wrote Father James Stephens, parish priest of Killybegs and Killaghtee in 1879. Today the pace of modern life and a move away from a pastoral society has resulted in the absence of men willing to devote time to church bell ringing.

The result is that the musical peals of real bells has disappeared, to be replaced by harsh tone-dead sounds emanating from church towers.

THE BELLS OF KILCAR

St Matthew’s Church of Ireland church in Kilcar has been long abandoned and roofless. The landlord, Murray Stewart, through his agent, G. V. Wilson in the White House, Killybegs, provided “a stove, a bell, and £18 towards the purchase of a harmonium” for this church prior to 1875. However, details of the bell’s manufacture, purchase, and erection have not yet been found.

With the excitement (?) of St Patrick’s Day 2022 just past and fast fading from memory it is almost too late to record an anniversary of the provision of a new bell for Kilcar old (R.C.) church. This building is now An Halla Paroiste. The bell was consecrated on St Patrick’s Day, 1882.

The Very Rev. Patrick Logue, P.P., Kilcar, purchased a bell from Murphys Bell Founders, Dublin, and it was installed in its new tower at the town end of the church. It was described as ‘sweet-toned and massive, weighing upwards of 27 cwt.” (1.4 tons) and “suspended in a belfry of elegant architecture, built of the famous fine-grained sandstone of Bavin”. The bell and associated works were estimated to have cost £300.

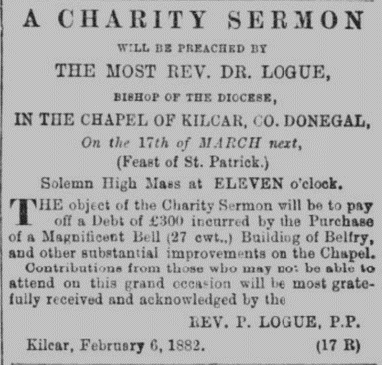

CONSECRATION OF THE BELL

On the day appointed, 17th March 1882, High Mass was celebrated in the old church by the Rev Francis B. Gallagher. His Lordship, the Most Rev Michael Logue, Bishop of Raphoe, was present, and preached a charity sermon, the purpose of which was to inspire the congregation to contribute to the costs incurred. The congregation was ‘large’ and included ‘not a few strangers from other parishes’. The music of the mass, taken from Webbe and Bordese, was ‘rendered effectually by the choir under the direction of Miss Martin who presided at the harmonium’. It was reported that ‘upwards of £170’ was collected within the church. In a list of contributors published later, it could be seen that the Killybegs contributions amounted to £16 12s 0d. while those of Kilcar totalled £12 16s 0d. This was no doubt offset by the contributions of those who attended the mass, who would have consisted of mainly Kilcar parishioners. A list of contributors was published in the press, these consisting of the more affluent citizens of the district. It might be said that many locals in the congregation likely paid more than some of the sums published, and it may also be remarked that a humble farmer or fisherman’s shilling was a greater contribution than some of the figures published?

KILCAR BAND PARADED

It was a gala day in Kilcar, with the local St Patrick’s Flute Band ‘gaily decorated in sashes of green and gold, carrying in front a large silk banner bearing the figure of the Irish harp, with the motto Eire go Bragh parading the town playing suitable music. (This band was in existence from at least 1875)

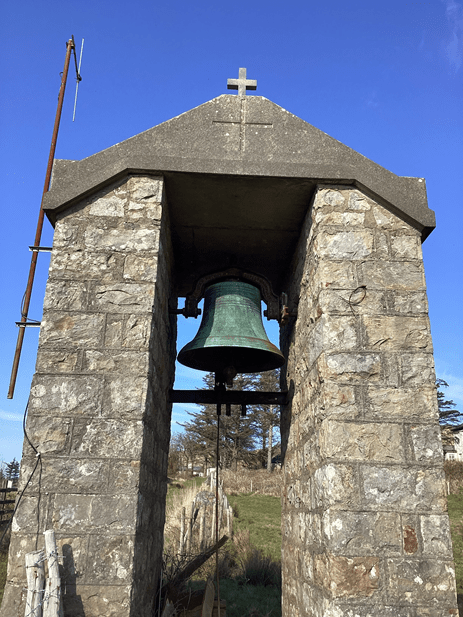

In 1904 when the present church was completed the 1882 bell was erected high on a hillside overlooking the town. It was said that “the bell was blessed so that as far as it could be heard nobody would be killed by lightning”. The task of transporting the bell from the old church to the high ground was entrusted to Hugh Chestnutt of Derrylahan. As the direct route to the new tower was too steep, Hugh had to take his horse and cart carrying the bell by the main road, and out along ‘the line’ turning left down to its destination.

CONDITION OF THE PEOPLE

Two years before this, west Donegal was reduced to famine conditions through bad weather and failure of the crops and fishing. At that time the Quakers were active in providing relief. James Hack Tuke of that persuasion toured the stricken areas of the west of Ireland in the spring of 1880. He called on the Rev. Patrick Logue, Kilcar, whom we found almost overwhelmed with the amount of work and extent of distress. Kilcar, we think, is, as a whole, the most destitute parish we have seen … they have no seed – some ate all their potatoes as they dug them up…. many families lying on the bare stone floor…….the fishermen have no boats and no tackle; little work was given (by the authorities) except the making of one road…

Now, in this year of 1882 crop and fishing failures had once again brought terrible suffering to south west Donegal. In Kilcar, the Rev. Logue, once again wrestled with the needs of his parishioners. On Christmas Eve 1882 he pleaded in the press for help for:

The poorest, most wretched creatures in God’s creation. We have 450 families in a parish of six hundred and fifty who are depending on the alms of a fellow man whom God has blessed with a little of the goods of this World. Two years ago hundreds of families of this parish were saved from starvation and death by the charity of the world. In 1847 the people had a little money, but no Indian meal to buy. This year we have the meal but no money, and, alas! no credit. I can see the plain proof (of famine) in the pale, shrivelled faces of many who crowd me for the price of a few pounds of Indian meal. As a priest I am in the habit of visiting the sick and dying in their hovels. I visit many who are in reality suffering nothing but from cold and hunger, and who send for me in the hope of getting some food. And, oh, what a sad picture to see their looks of disappointment, misery and despair when I tell them my poor funds are exhausted. The severe frost and awfully inclement weather have made the hopeless prospect more hopeless still in their cold and comfortless cabins… half the individuals in this parish are strangers to the comfort of shoes or boots. Add to this the many poor starving creatures who, from morning to night besiege my door moaning and wailing their utter state of wretchedness. These poor, wretched creatures, when asked when did the potatoes give out, say: ‘I had not a potato since the 1st of November’. How did you live since? ‘After my children went to bed I sat up and did a little sprigging which brought me a few pence’. Have you any potatoes at all? ‘Not one, we ate the seed before we would die with hunger’. Have you any animals for sale? ‘No, I have not even a hen’. And how will you live until the middle of August next? ‘God alone knows …. I would be willing to draw stones on my back to earn a few pence to keep the children from starving’.

What am I to do among such misery? I would ask for the sake of humanity those with a little to spare to send their mite and rescue from the pangs of hunger the most honest, virtuous and moral people on God’s earth.

It is nothing short of astonishing that part of those ‘few pence’ from sprigging went to pay for the church bell. It says much for the strength of faith in that Kilcar that such pennies were so freely given.

Lest it be thought that Kilcar parish was exceptional, it should be said that the dwellings and circumstances of the ordinary people in west Donegal at that time were broadly similar.

‘

This blog was written with the kind assistance of:

Maeve McGowan, Killybegs, Peter Molloy, and the Kilcar History & Heritage Group.

The staff of Aislann Chill Chartha were more than helpful.