Stories of Killybegs Railway, Part 4.

The 130th anniversary of the Donegal-Killybegs Railway occurred in August of this year.

Railcar No 12 at Killybegs, 17 May 1959, ready for Strabane.

NO RAILWAY FOR ARDARA

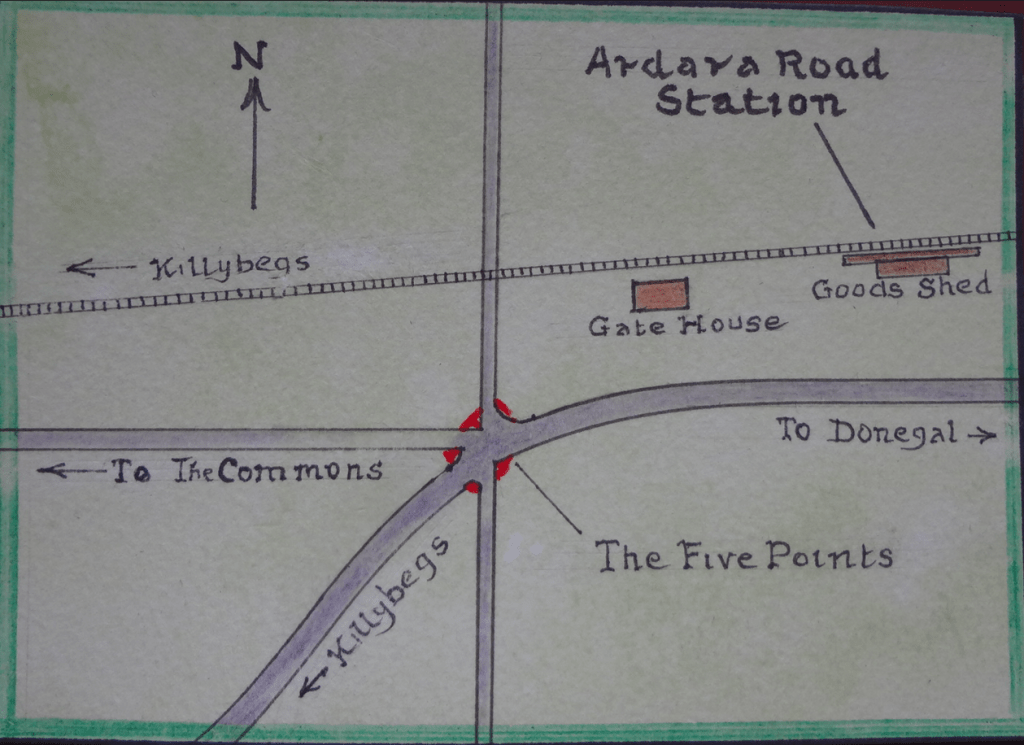

Although there was a proposal to lay the railway to Ardara, this did not happen. The parish priest of Ardara, Rev. Bernard Kelly, was a strong advocate of a line to Ardara. He stated that the railway would help to develop the fisheries at Rosbeg and Ardara, which had no means of export except by cart to Killybegs, where Mr Drummond iced the salmon. (William Drummond was the leading fish merchant in Killybegs in the 1890s; he owned an extensive grocery and hardware store located in the building now occupied by Mrs B’s café). The original plan was to take the line from Glenties to Killybegs via Ardara, in two sections. The first section was to be 15 and two eighths miles long, from Glenties to Killybegs town. The second was to be two furlongs in length, from the town down to the harbour. The estimated cost of the first was to be £90,057, and the second £3,349. There were to be a stations at Ardara, Meentullynagarn, and Killybegs. This proposal was abandoned, and it was said that the Ardara people missed an opportunity of lobbying for an extension from the Ardara Road Station to their town. The Station which would be called Ardara Road was established in 1910.

SHOCKING ACCIDENT AT ARDARA ROAD STATION NEAR THE FIVE POINTS

It was here in 1902 that a passenger, Peter Boyle, was killed soon after he disembarked from the train, being practically cut to pieces. Mr Boyle, who was about fifty years of age, and from Meenavally, left home on the morning of Thursday 3rd April for Donegal, where he transacted some business. He returned by the evening train, arriving at Ardara Road Station at eight thirty six. At a distance of 108 yards from the station two gates closed off the old public road to Ardara when the train was due. These gates had lamps which were lit at night. The Station and the Station door were lighted.

The Stationmaster, Jim Walker, said later that ten or eleven passengers, including Mr Boyle, got off the train. He thought that Boyle had remained at the Station also, as he had to pay him for the ticket to Donegal and back. He (Walker) did not have the change in the morning when starting off. The deceased appeared to be sober; he walked along the path towards the gates and the road home. The other passengers did not leave the platform until the train had departed. The night was stormy with hail showers.

The driver said he blew the whistle while starting off. When the train was crossing the road the driver, Sam Jones, thought that there was some gravel on the line. He applied the brakes, and when the engine stopped the fireman, James Duffy, got out with a hand-lamp but saw nothing unusual. The journey was continued for a short distance but the driver told the fireman that there must be some stones on the line. Duffy disembarked again and informed the Stationmaster. He examined the line as far as the last Gate-house before Killybegs. (This Gate-house at Straleeny was then occupied by the Sweeney family; later by the Hegarty family). He found a parcel and some money between the rails at a point 210 yards from the Ardara Road platform.

Charlie Sweeney from the Straleeny Gate-house, and Bill Walker also joined in the search. They were horrified to find the mutilated body of Mr Boyle, lying on its back between the rails, with some of the limbs missing. The police were called, and a further search revealed one of the man’s feet at a distance from the body, while the track for about a hundred yards was strewn with pieces of flesh and bone. Sergeant Fallon of the RIC, while searching the line, found a walking stick, some sugar, a muffler and portion of a sock. He spent over three hours collecting the remains.

It was thought that the man was walking between the rails when he was knocked down and dragged along the line. The remains were taken to Killybegs.

Railcar No 20 at Killybegs Station, 1956. (J. G. Dewing/Ernie’s Railway Archive)

RAILWAY PASSENGERS FINED

At Killybegs Petty Sessions in 1918 two Ardara men, Daniel —– and Patrick —— of Bracky, were fined for ‘having travelled on the railway on the 5th January, between Ardara Road Station and Killybegs Station without having paid their fares, and failing to produce tickets.

Their defence was that they had paid for tickets from Donegal to Ardara Road, which was the stopping place on the line for Ardara passengers going home. They claimed they were over-carried. In those days the Guard on the train would call out the approaching stations so that people would know where to get off. However the men stated that there was no shout, and that they were carried on to Killybegs. John Sweeney, the Guard, and Joseph Murray, Stationmaster at Killybegs, gave evidence, and the men were fined ten shillings each, with an additional one pound costs.

CALLING OUT THE STATION NAMES

The late Bertie Boyd used to tell a story about the Guard calling out the name of each approaching station. Two farmers from Tullaghacullion decided to travel to Dunkineely, and got on at Ardara Road. They asked the Guard how would they know when the train had arrived there. He told them he would shout out ‘Dunkineely’ when they were getting near. A couple of ‘corner boys’ from Killybegs, who were in the carriage, were listening to this, and when the train was approaching Bruckless Station they shouted out ‘DUNKINEELY’, and the men got off at Bruckless.

You must be logged in to post a comment.