The Lobster War — or how the Frenchmen were finally run to ground off Donegal

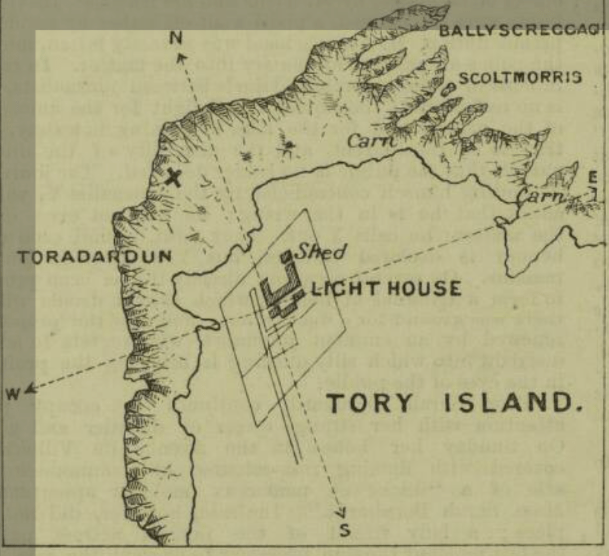

When Napper Tandy landed at Burtonport in 1798, he arrived just in time to hear the thunder of defeat echoing from the Donegal coast, where the French fleet had been shattered. One hundred and thirty-eight years later, history—smaller in scale but no less spirited—prepared to repeat itself. Once again, French vessels would come to grief in the waters of Donegal.

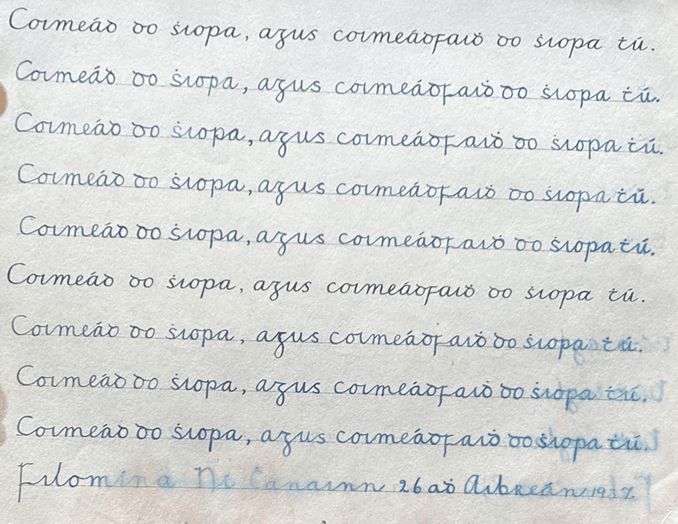

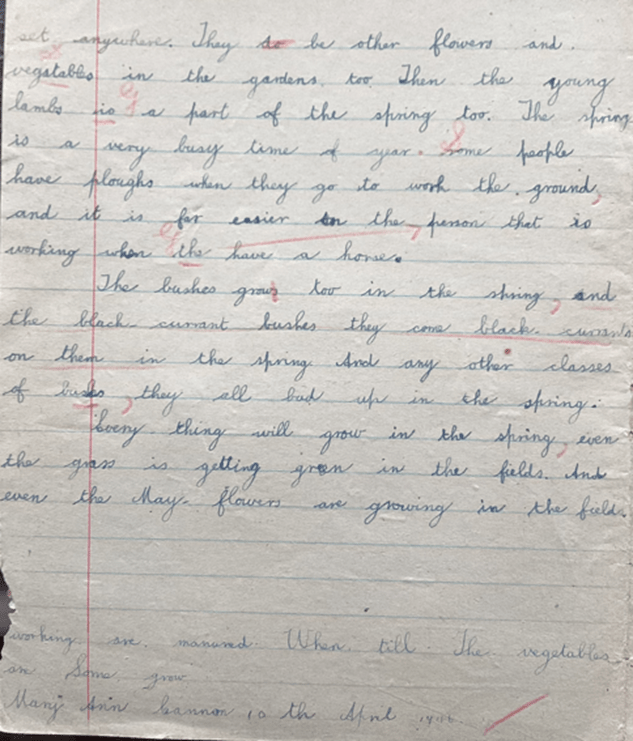

French-style pots

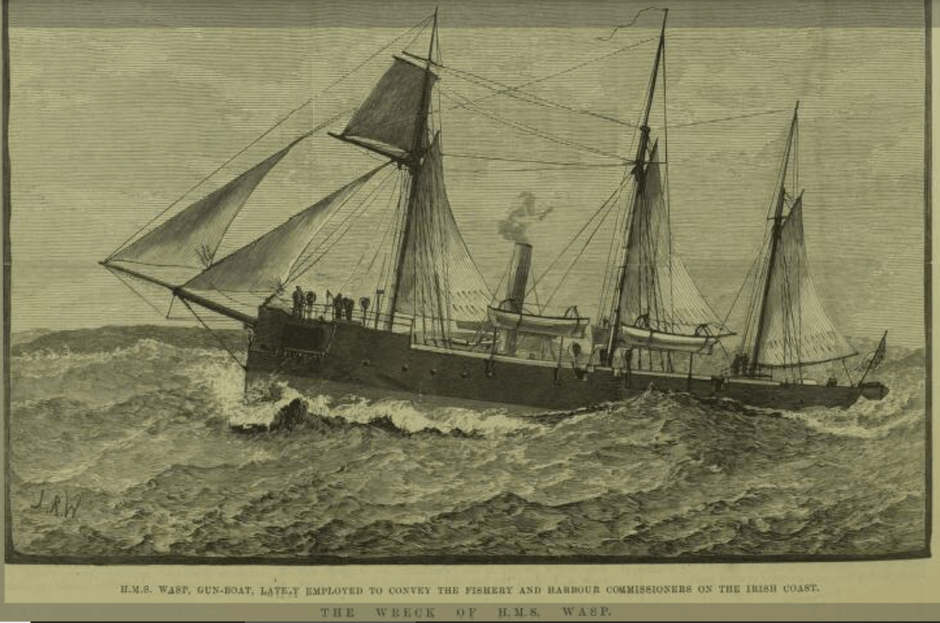

For years, the French well-boats had haunted the Irish coast like silent predators, prowling for lobsters and crawfish. They grew bold in the 1930s, emboldened further when Britain had withdrawn the last of its patrol cutters in 1923. With only a lone fishery protection ship—the ageing Muirchu—the Irish Free State struggled to defend its long coastline.

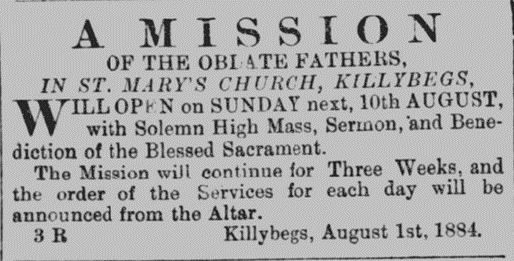

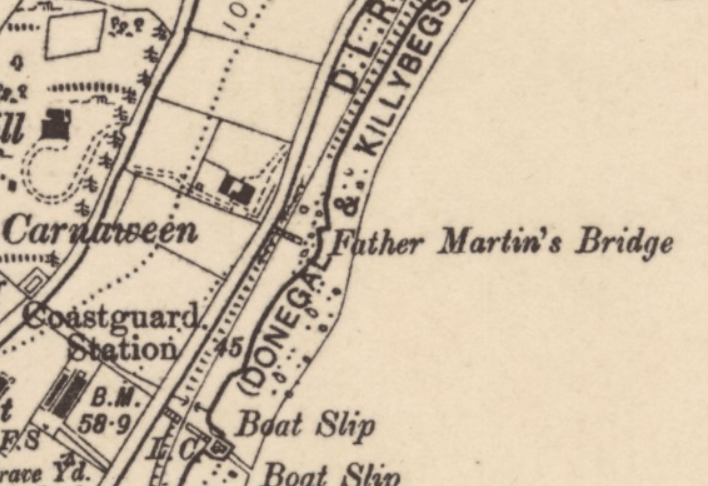

English trawlers were brazen enough, but the French were thieves. They plundered lobster pots openly, guns at the ready. Fishermen who dared intervene were met not with words but with gunfire. The French lifted Irish lobsters, set their own crawfish pots, and vanished over the horizon with their living cargo held in well-tanks. The Muirchu made her coal-runs to Killybegs, but each year she vanished to Birkenhead for repairs, leaving the coast exposed.

So, in the summer of 1936, Donegal lay undefended—its waters free for the taking. Or so the raiders believed. They had not reckoned with Garda Superintendent Tom Martin.

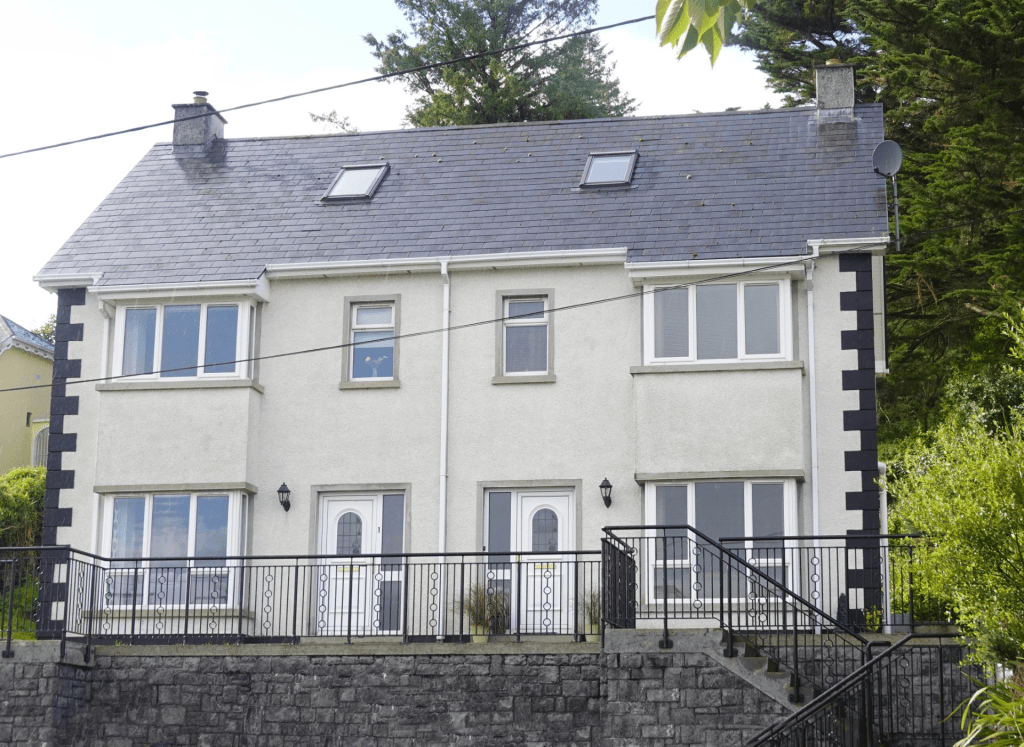

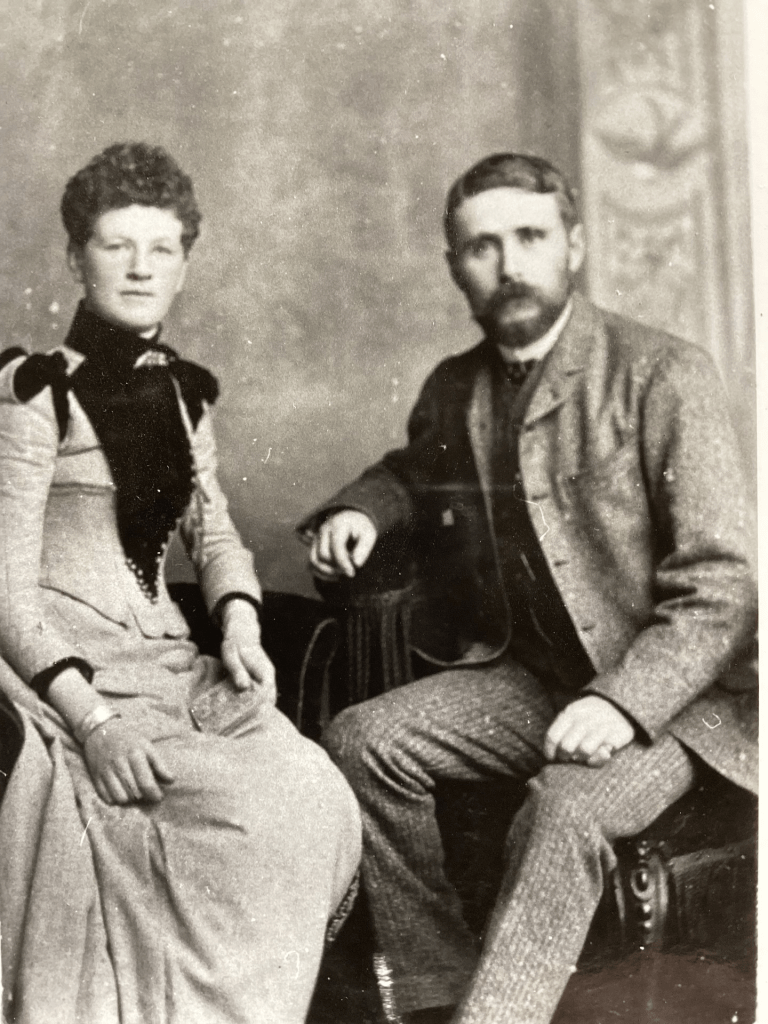

Recently posted to Killybegs, Martin was no ordinary official. A former old IRA man and Flying Squad veteran, he had once hunted the Black and Tans through the countryside. Now he was in charge of a newly strengthened divisional headquarters—one sergeant and six guards—and he intended to defend Donegal’s waters where the Navy could not.

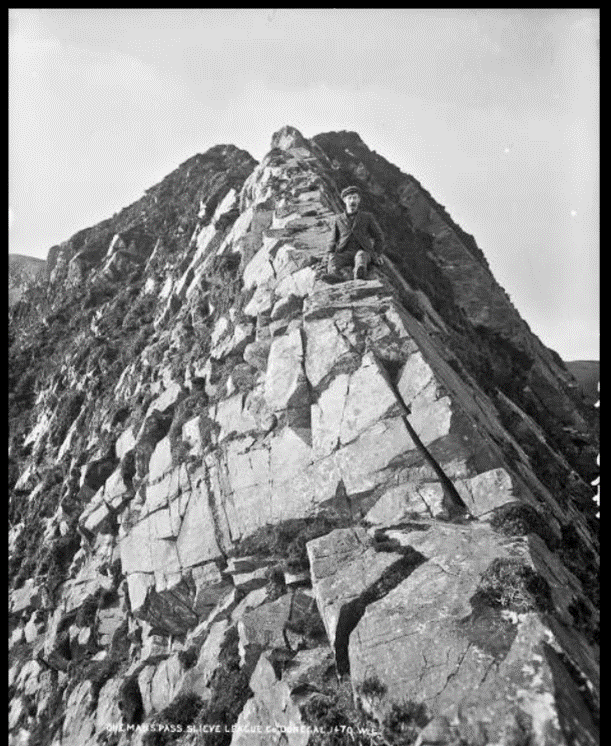

As foreign trawlers once again descended—whitefish to Fleetwood, shellfish to France—Donegal’s fishermen watched helplessly. But when two French well-boats were spotted at Glen Head emptying pot after pot, word reached the Guards. The French skippers were already named: François Saladin and Yves Kersalé.

The Glen sergeant asked permission to give chase. Martin’s answer was simple: he would lead it himself.

Dingle men to the rescue

But first he needed a boat—and no Donegal skipper would risk his livelihood, or his life, against armed Frenchmen. Salvation came from the south: a handful of Kerry fishermen working from Killybegs, who knew French piracy all too well from their own coast. They stepped forward without hesitation.

Martin hired the Naomh Ruairí, newly built in Killybegs Boatyard for Tommy Brosnan of Dingle—a sturdy, carvel-built craft, fully decked and rigged for both sail and engine, a rarity in those waters.

On 23 July 1936, Martin and his armed Guards boarded her, Lee-Enfields slung over their shoulders, and steamed out of Killybegs. Off Teelin, the fugitives were sighted. Signals were ignored. Martin fired a warning shot across the bow. Still the French pressed on.

Then came the volley.

Gunfire cracked across the water. The French skipper pretended to surrender—only to throw up sail at the last instant and open fire on the Naomh Ruairí. Bullets whistled through her rigging. The Guards returned fire, but the Frenchmen fled north through the Sound of Rathlin O’Beirne and making for Arranmore.

But this time Donegal was ready. Gardaí in the Rosses had been alerted. When the French approached Burtonport, thinking themselves safe, armed Guards were waiting. The crews were arrested; the boats seized and towed in triumph into harbour.

In court the charges were: fishing in prohibited waters, improper markings, unlicensed firearms. Saladin was fined £82, Kersalé £66; both lost their catch and their gear. Held in Burtonport barracks, they cooked their own meals and threatened hunger strike as their solicitor, Pa O’Donnell, appealed desperately to the French Consul.

At last, on 4 August, the fines were paid. The boats were released, and the skippers allowed to buy back their equipment for £15—a final indignity.

Jack Barry prosecuted; L. J. McFadden defended, with J. W. McLean of Dungloe interpreting the Breton French. The diplomatic ripples travelled far enough that a French fishery-protection ship, the Quentin Roosevelt, appeared off Donegal weeks later—a polite reminder that France, too, could show the flag when required.

Superintendent Martin settled in Killybegs for life, respected in the courts and in the town’s cultural life. He never lost his ease with a rifle. Even in retirement he was a hunter—foxes replacing Frenchmen. In 1937 his little fox terrier became a legend in its own right, killing five foxes in a single outing at Stonebrook, Loughros Point.

And so ended the last great sea chase of the Donegal lobster wars—fought not by navies, but by fishermen, Guards, and one determined superintendent who refused to yield Ireland’s waters to foreign poachers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.